Respect is less about how we feel about our people and more about what we do for our people!

So many work processes are performed “unconsciously” in the sense that they are done without a clear understanding of the key steps, degree of expected quality, how much time they should take, and how difficult the work should be. Beyond treating people well, respecting people is about being thoughtful and intentional about the work experience of the people you lead. When organizations leave work totally undefined, they leave it to each person to try to figure out the best way to do the work based on their own singular, personal opinion. This usually creates a chaotic mess.

Recently, I was working with a large tech company whose new customer onboarding process was a combination of tribal knowledge and make-it-up-as we-go work processes. After doing a thorough virtual “go and see,” it was clear to me that everyone was suffering, including the people doing the work and new customers who were shocked by the delays, uncoordinated communications, and the overall disappointing experience.

I asked the leader who I was working with, “What kind of a message do you think this sends to your people and your customers?” “We don’t really care about you!” was his reply. I think he nailed it… When work processes are left undefined and open to personal opinion, we send a strong message to people: “We accept the status quo, so do your best with our broken processes.”

When I am coaching leaders and team members, I often ask, “How long has this process been broken?” Invariably I hear, “As long as I can remember,” and “It’s always been that way,,. so we’ve learned to make it work.” But trying to make a broken process work means wasteful extra steps, mistakes, rework, interruptions, and highly variable flow of the work. It also means there is little stability around the time it takes to deliver and the quality that the customer receives. No one is happy; frontline workers live in fire-fighting mode while customers encounter a broad range of unpleasant purchasing and customer support experiences.

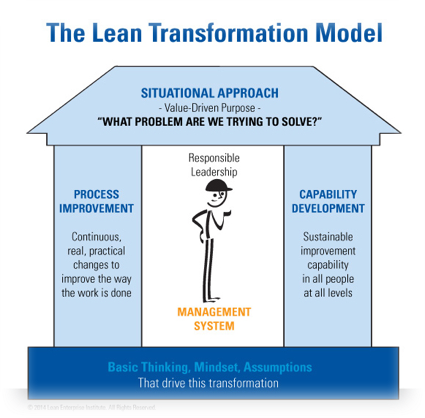

In response to the problem, we gathered a team to work on a rapid improvement effort around the new customer onboarding process, employing lean methods and tools. The team came together and worked so well that they completed eleven PDCA learning cycles across four A3s in a period of seven months. The results were amazing in terms of customer feedback and satisfaction, work performance metrics and teamwork!

The team celebrated briefly only to discover that improvement work was not a one-time effort. It became painfully obvious that the process for this and every other type of work needed to be adjusted and improved on an on-going basis in perpetuity! When I asked the leader and team members for key insight and takeaways from this experience, the common recognition was that:

- Work processes need to be defined, shared, and honored by everyone doing the work

- It was not enough to improve the work once; ongoing improvement was essential

- Teams needed to be deeply involved in the improvement effort, but also needed support from their leaders and someone who knew lean thinking and practice

- None of the other points really matter if the people who are doing the actual work do not feel respected by their leaders

- The best way to show respect is to enable team members to improve their own work processes as a central element of their daily work

So what concrete actions can leaders take?

- Go and See – spend time with your people doing the daily work on the front lines to understand what it is to stand in their shoes and do the work

- Identify the core work processes that the team performs (just ask folks!)

- After watching, asking, and observing, ask yourself, “Is this work process stable, commonly applied, predictable, and effective?”

- If not, ask the team to answer the question, “What is the problem we need to solve?”

- Create an opportunity for the team to hold an improvement event (aka Kaizen event) with adequate support and coaching for them to be successful.

In short, honor the work of others by honoring their work experience. As a leader, when you take the time to deeply understand the challenges your team members face and the impact this has on teams and customers, you will demonstrate more respect for people while driving improved performance. This is a win-win for the customer, the team, and the entire organization.

Ultimately, it is not what you personally think or feel about the idea of respect that counts; it is about what you actually do to support your people. Demonstrate your respect for others by