The focus of our work and teaching in recent years (Mindful Coaching, Helpful Coaching, Leading with Respect, Humble Inquiry Questioning, Coaching for Development) has led us to three questions we believe are critical for the Lean/ Continuous Improvement community to consider:

- Why would a practical business leader like Fujio Cho make “Show Respect” the third part of his advice to leaders?

- What is “Psychological Safety” and how does “Show Respect” help create it?

- What does Neuroscience research indicate about the link between “Show Respect” and “Psychological Safety?”

1) Why “Show Respect?”

Mr. Cho urging leaders to “Go See” and “Ask Why” makes sense as part of basic Toyota problem solving thinking. You want to grasp the actual conditions rather than assume you know, and you want to dig down to the underlying causes of problems rather than put band-aids on the symptoms. But why is “Show Respect” so important for Mr. Cho? Is it just because he’s a nice guy? (The team members at the Georgetown Toyota plant in Kentucky certainly felt he was when he was president there.)

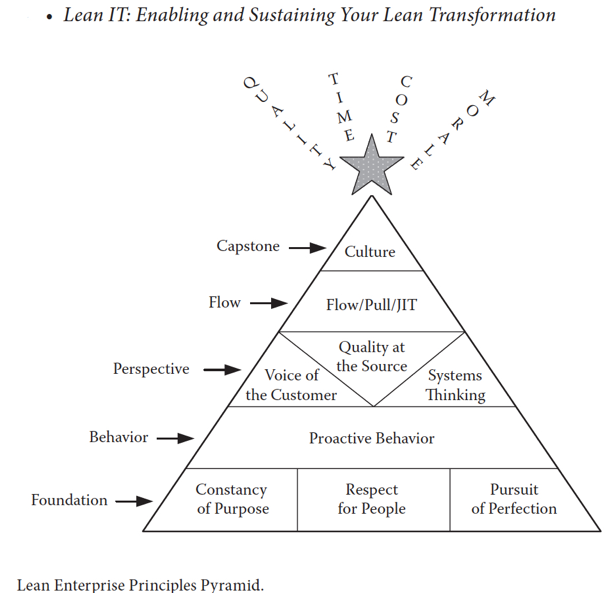

We believe there is a practical business reason why Mr. Cho stresses the importance of leaders showing respect for employees. And it goes beyond the focus Toyota puts on the employees who do the work that creates value for its customers. Remember that when Mr. Cho was President and CEO of Toyota Motor Corporation (all of Toyota world-wide) he led creation of the first authorized description of the Toyota Way. Images such as the one shared above are often used to illustrate the key elements of the Toyota Way.

In most depictions of the Toyota Way, the fundamental values or pillars are the same, Continuous Improvement and Respect for People.

Mr. Cho was being very practical in his focus on “Showing Respect” as a critical management and leadership practice. If Continuous Improvement is the pursuit that helps a company solve problems, improve performance and adapt to challenges of change, Respect for People is the key to engaging employees in continuously making and sustaining improvements that makes it work. A company cannot afford enough managers, supervisors and specialists to address all the small things that need to be improved to maintain smooth flow and effective operation. The employees who do the value creating work have to willingly take on that responsibility. Employees who do not feel respected for their knowledge, capabilities and contributions are not likely to make the effort to go beyond assigned tasks and responsibilities very often.

Many in the LEI community who are involved in trying to overcome the obstacles in the cultures of their companies and engage employees in continuous improvement as part of their jobs have intuitively recognized the importance of leadership “Showing Respect” for their efforts. But we have not been successful in demonstrating to leaders and executives how their traditional management thinking and behaviors undermine their desire for the benefits of employee engagement. We hope to provide a first step toward making the case with this article.

2) What is “Psychological Safety” and how does “Show Respect” help create it?

The freedom to be yourself without fear of judgment is, in our opinion, the most significant obstacle to creating a culture of deep learning and continuous improvement.

In virtually all organizations, physical safety is a given. Most governments protect workers from the risk of accidents by enacting laws and regulations covering building codes, fire safety, ventilation, hearing and eye protection, gloves, hard hats and steel-toed boots. And most companies have programs that stress the physical safety of their employees. But there is another kind of safety that is just as critical as physical safety. It is psychological safety and we believe it has an incredible impact on an organization’s culture and the way people behave and think about their work, their colleagues and the interdependent aspects of their jobs.

In her new book The Fearless Organization, Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson defines psychological safety as “the belief that the work environment is safe for interpersonal risk taking. The concept refers to the experience of feeling able to speak up with relevant ideas, questions, or concerns.” This quality is invisible, seldom managed well and, when neglected, highly influential on employees’ understanding of their role and place in their companies. The critical question is, do employees feel it is a reasonable personal risk to speak up or not just go along?

Why is psychological safety so difficult to foster and maintain? There are many factors, but perhaps the most significant one is the way our brains are wired. Most people crave positive recognition and appreciation while avoiding criticism. We tend to be very concerned about what others think of us. We are often overly reactive to negative feedback and those who disagree with our ideas. (More on why this is so in Part 3: What does Social Neuroscience research indicate about the link between “Show Respect” and “Psychological Safety?”)

For people to engage at a much deeper level, they must feel instinctively comfortable being themselves and sharing what’s inside (ideas, concerns, ambiguities, unknows, uncertainties, hunches, etc.). This may seem obvious, but when we cannot be ourselves, we expend most of our attention protecting our image rather than engaging in meaningful dialogue! We are careful with our words, don’t talk about mistakes and withhold information – all with the purpose of managing what others think about us! This takes an incredible amount of energy and focus. The effort drains us of the spark we need to be creative, be open-minded, hear dissenting ideas and process tough feedback.

In her numerous studies of high performing teams Edmondson learned another fundamental aspect of psychological safety: it’s primarily local. The social environment in teams and groups can vary widely across organizations. The overall culture in an organzation is a factor but it is the sense of safety within a group that is the main influence on how willing members are to speak up and speak out. And the greatest determinant of the sense of psychological safety in a group or teams appears to the behaviors and assumptions (i.e. leader knows, decides, tells) of the leader. What the leader does, does not do, expects and will not accept sets the time for the team. Edmondson’s findings are supported by a two-year Google study of performance and work environment of a 180 teams (Project Aristotle). The local leader is the primary source of members’ assumptions about the balance between fear versus safety that infleunce their sense of what is and is not a reasonable personal risk.

Continuous improvement is more difficult than anyone seems to want to admit because it’s continuous! This requires amazing reserves of drive, passion and stamina to persevere through the inexhaustible challenges, countless iterations of trial, discovery and learning, and the inevitable failures that must be embraced if we are to learn, improve and make meaningful change.

Without psychological safety, a team, a department and an organization are severely handicapped because they are deprived of the full contribution each person has the potential to provide. With psychological safety, people share everything they have to give, and everyone – and the company reap the benefits.

3) How are “Show Respect” and Psychological Safety linked?

In keeping with basic lean thinking let’s look beneath the outcome of Psychological Safety for the human processes that create or destroy it.

Neuroscience research has made significant gains in understanding the things that happen in the structures of our brains during different human activities. Using functional MRIs available since the 1990s it is possible to observe what happens inside the brain during both cognitive processing and social responses. Functional MRIs show movement of blood in the brain which indicates neural activation. In other words, neuroscientists scientists can now see which parts of the brain are engaged in specific brain activities. These insights demonstrate how respect and trust contribute to a sense of psychological safety and how their absence makes us afraid of taking risks in social situations.

Physical pain and painful social situations activate the same pain neural network and in much the same way. When we have physical injuries or experience social pain such as rejection, humiliation, embarrassment or criticism our brain reacts to them with similar physical sensations and emotions. That means we experience emotions and social pain in and with our bodies.

As an example, please close your eyes and think of a particularly embarrassing or humiliating moment in your teen years. How does your body respond? Most people experience a physical reaction such as a tightening stomach, flushing, tingling or tightening in the face, a feeling of distress. Many jerk their heads or bodies to try to shake off or get away from the feelings. The later is a flight response because your threat network has also been activated also and you experience the memory as a danger to you socially. Also consider how we describe the impact of such social situations: “I was crushed. She broke my heart. It was a real blow.”

Outright rejection of us or our ideas; angry or harsh criticism (especially in public), exclusion from an ingroup or inside information, the humiliation of a public put down, being discounted, disregarded or taken for granted, and being bypassed through favoritism all trigger some form of pain reaction in our bodies and some degree of feeling unsafe or threatened. Over time, experiencing these “social injuries” or seeing them inflicted on others creates impressions of “that’s what to expect around here.” Over time those impressions become unstated assumptions and form our unconscious recognition, and that of our group, of the culture of the company or organization.

Such an implicit understanding of our work environment is critical because it leads to other assumptions about whether it is safe to speak up, make suggestions, point out problems, disagree with management and your peers. If we do not feel we can risk speaking up, stepping up, reaching out, pointing out and suggesting it is very unlikely we will commit much continuous time and energy to addressing problems and working on improvement. If we do feel safe and respected and valued for our capabilities it is much more likely we will see it as a reasonable risk to exercise discretionary effort (meaning to go beyond what can be required or demanded) and willingly engage in continuous problem solving and performance improvement.

There is another important aspect of the brain activity related to our social lives. Pleasant physical and social experiences also activate the same reward network in our brains. That means when we sense we are included, valued, useful or given meaningful responsibility it is not just an idea, it is also a pleasurable and rewarding physical experience. Think of expressions we use to describe these moments: “Helping him warmed my heart. It gave my spirit a real lift. I felt 10 feet tall when she handed me the award.” The implication is that what we are experiencing is both physically and socially rewarding. Our human need to feel connected and accepted is being met. This makes it much more likely that we will feel safe exercising our discretionary effort and willingly take responsibility for contributing and making things better.

The equation for Discretionary Effort is simple but getting it to add up is difficult: Respect + Acceptance + Trust = Psychological Safety.

Mr. Cho was right about the importance of RESPECT. Rodney Dangerfield complained he couldn’t get any. Aretha Franklin demanded it. According to researchers, acceptance, trust, respect and being useful were originally critical to our survival because they meant inclusion – and safety – in the family or social group. In our brains they are still essential in our new “families” and “communities” – our companies and organizations. Without this social “security” we don’t feel we can take the risk of contributing aswe are able. When respect is not demonstrated and a sense of psychological safety is not part of the culture, we are destined to see struggles such as many companies are having engaging employees in continuous improvement activities and sustaining their involvement.sustaining their involvement.

A collabroation with my good friend David Verble.